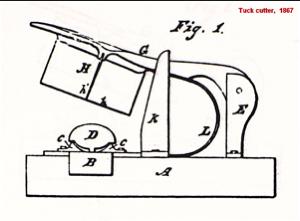

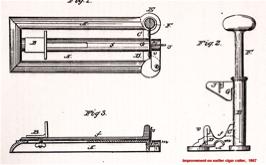

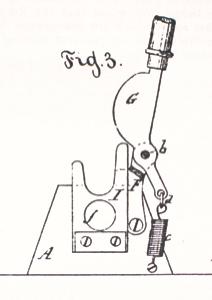

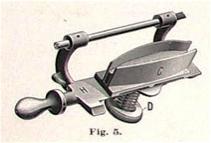

Cheroots are made in two parts, filler and wrapper, the latter applied perpendicular rather than on the diagonal like the three part cigar. Cigars normally have a closed head and open tuck, where cheroots are shaped more like cigarettes, straight-sided with both ends open,

hence the practicality of this cutter. [5245]

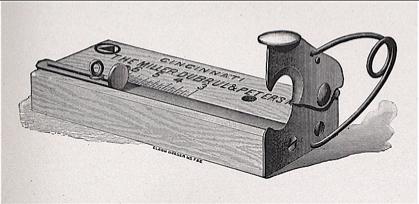

![That popular and mechanically simple model (called a “Union Cutter” by MD&P) was used in 3 ways: [1] as a stand-alone; [2] the block could be bolted to a cutting board or table top; or [3] the cutting apparatus could be attached directly to a board as seen above. [N1207]

A stand-alone version attached to a block of wood cost 60¢ in 1904.

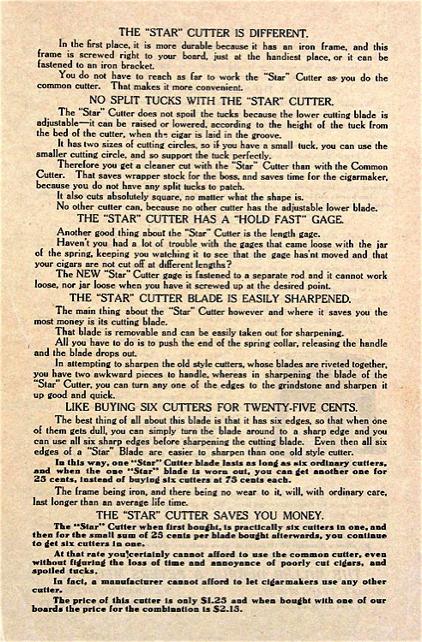

Although cutter designs were modified often, the only great design revolution came with the introduction of the MD&P Star Cutter in the 1880’s.

Touted advantages included cast iron frame, adjustable lower blade preventing crushing, six blades in one to decrease down time and damage when one becomes dull, removable blade easily sharpened or replaced, and the length gauge less likely to slip.

Not mentioned, but important for user convenience, the redesigned handle made for smooth comfortable operation.

Cutter and board cost $2.15 and new blades a quarter.

[4829] [N1207]

[4828]](Hand_tools_files/shapeimage_2.png)

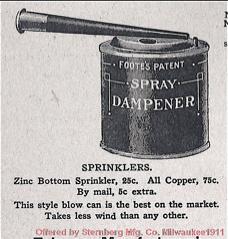

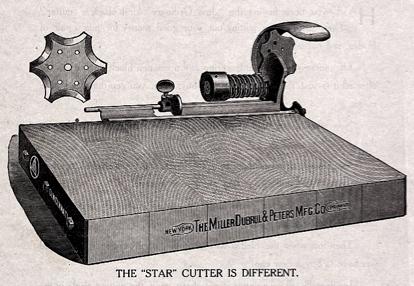

![Tuck Cutter (also called a Cigar Cutter)

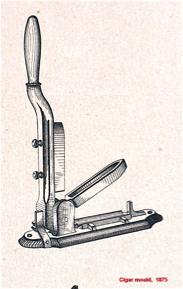

Cigar making is a very repetitive process. Over and over, hundreds of times a day, the exact same dozen actions are performed. Anything that can be done to make one of those actions easier, faster, more efficient or more exacting puts money in the pocket of both the roller and factory owner. Let’s face it, cigar rollers didn’t do this for romance; cigar making is a JOB ... a job that pays piece rates. The more and better cigars you roll, the more money you make. Speed and efficiency are important.

One of the myriad steps involved cutting off the end of a hand made cigar to open an end for lighting (creating the tuck, the opposite end from the head) and at the same time trimming a batch of cigars to uniform length. Uniform length wasn’t critical in the 1700’s or early 1800’s because cigars were seldom packed in consumer size boxes; when they were, the boxes were sold closed, the cigars unseen. But after the Civil War, when boxes were required, cigar length became critical. Cigars had to fit in the box. Cigar boxes and cigar length are specified in

1/16ths of an inch, and in some cases by 1/32nds. so an accurate cut was important.

Using an ordinary roller’s knife for this operation often resulted in a crushed end on the cigar. It became necessary to have a knife that would support the bottom of a cylindrical object while it was being cut from the top. A knife that could also guarantee uniformity of length would be perfect. Hence, the “tuck cutter.” Early catalogs often call this tool a “cigar cutter” but I prefer the more descriptive “tuck cutter” to differentiate it from the pocket or counter-top cigar cutters used by smokers to open the mouth-end of a cigar.

[4911]

Lots of cigar workers had ideas how to solve the problem so patents and custom made tools abound. Each manufac-turer came up with variations, but one of the most popular was designed a few years after the Civil War and manufactured for half a century. Note that measurements go from 3 to 6 inches, standard size for a 19th century cigar.](Hand_tools_files/shapeimage_3.png)

![Tobacco Sprinkler

At various times in the manufacturing process it is necessary to moisten tobacco. Simple blow cans are used, emitting a fine spray. A few different models were offered, generally operating on the same principle. This example, the same as the cigar-tool king Miller, DuBrul & Peters offered under their name, was advertised by the Sternberg Manufac-turing Company in Milwaukee in 1911.

.

Another tool company offered a sprinkler attachment to “fit any ordinary bottle” pointing out that bottles are easily cleaned, don’t rust and the contents can be seen. Their comment about rust is particularly meaningful given the rusty condition of the Museum’s example. Their ad neglected to mention bottles broke, and were more likely to tip over.

[4926]

[11545]

[4868]](Hand_tools_files/shapeimage_4.png)

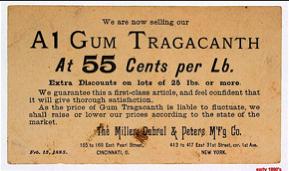

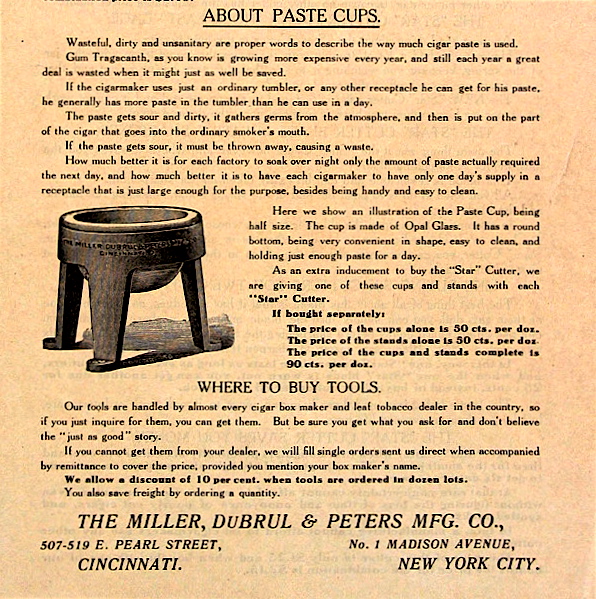

Gum Tragacanth (cigar glue) and a Paste Cup to Hold it

[4824] [4823] [4827 below]

Mythology has long accused cigar makers of twirling cigars in their mouth, using saliva to secure the head, and there is evidence to give credence to the legend. Certainly early cigar rollers, especially those making cigars for their own consumption, did exactly that. But by the time cigar production became factory-centered in the first half of the 1800’s, the heads of cigars were almost universally held in place by gum tragacanth bled from the tap root of Iranian loco-weed and dried.

Tragacanth is odorless and tasteless and when added to water becomes a gel used in foods, art, medicine, cosmetics and cloth manufacture as a stiffener, binder, thickener and glue. The cigar industry used it as a paste for two centuries. Trade relations with the middle-East have always been volatile and so has the price of the gum. That’s why this 1885 ad warns that prices are subject to change. Today, because of worsening relations with the middle-east and the ability to cultivate other gums in the western hemisphere, gum tragacanth has largely been replaced in most U.S. commercial applications.

In Latin countries, stickum of various types goes

by the generic goma.

paste cups as part of a package. I do not own one of these

tripod-cup combinations to display. Cigar rollers, who

supply their own hand tools, frequently use glass furniture

castors as paste cups. [11533]

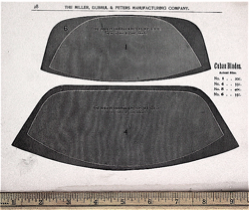

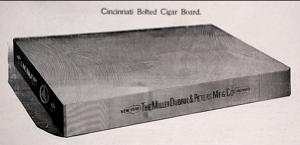

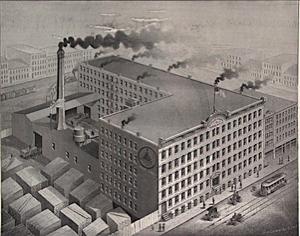

Cigar Board

This descriptive page from the 1904 Miller, DuBrul & Peters catalog quotes boards at $1. Other manufacturers sold them in quantity as cheaply as 50¢. The National Cigar Museum owns company files from Bedortha and other tool makers that indicate a high number of quality complaints for cheap tools, a sentiment most modern workmen, no matter the field, will echo.

By the 1840’s, illustrations depict the cigar roller working on a three-sided cigar maker’s table with only two tools, a board and a kitchen knife.

[10377]

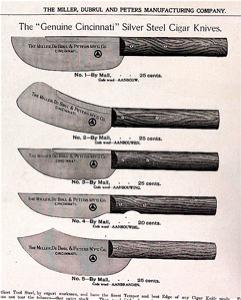

![Chavetas & Knives

The first logical addition to the cigarmaker’s tool bag was something to cut with. Flat handleless knives called chavetas were fashioned from scrap metal and sharpened. At first home made, these simple tools were soon commercially fabricated, though when and by whom this was first accomplished is unrecorded. Dozens of different sizes and shapes are known; cigarmakers sometimes ground their chaveta to a custom size or curvature. This flat blade became the cutter of choice throughout the Caribbean and was called by gringos, a “Cuban blade.” Prices in 1900 ranged from 20¢ to 40¢ each.

Knives with handles, called cigar knives, costing around a quarter in 1900, were more common, used by most cigar rollers. They were available in a wide range of shapes, allowing rollers a great deal of flexibility in how they worked.

[4896] [11167]](Hand_tools_files/shapeimage_5.png)

The First Tool: A Rock

An early 1800’s chronicler of cigar manufacture wrote: “The outside of the cigar is made of one or two leaves, beaten flat by small smooth stones. They are filled with smaller pieces, rolled, and cemented on the edges with a pink paste.”

This seems a rather brutal approach, and must have resulted in a great deal of damaged tobacco, yet, amazingly, rocks were still reported as being used in some southeast Asian cheroot factories as late as 1890. Neither report detailed exactly why and how rocks were used. The best supposition is that it was to flatten the midribs.

[0490]

This 1827 British satire is the earliest depiction of cigar rollers of which I am aware, and shows them working without tools as the natives of the New World did for centuries.

Of course, a print created by a British artist who had most likely never been to the Caribbean is of questionable historic accuracy, and can be considered suggestive only.

[0141]

White by his left hand is a blemish in the print, not a tool.

This exhibit looks at two dozen hand tools found in the typical cigar factory. Visitors who want merely to know the names of what they have so they can sell them in their shop or on ebay® will find the most common tools pictured here. More information on each is below.

Cigar Hand Tools

A National Cigar Museum EXCLUSIVE

© Tony Hyman with the help of

retired cigar maker, Bob Frutiger

Cuban blade or chaveta

Cigar maker’s knives

Cigar board with

attached tuck cutter

& replaceable star blade

Tuck cutter

comes in many variations

Cigar mold or mould

comes in 3000 variations

Paste cup

n.t.s.

Bundling rack

comes in many variations

Mould press also

comes in desk top model

Packer’s press with lever

also comes without

Cigar packer

other variations exist

Packer’s box

Cancellation date stamper

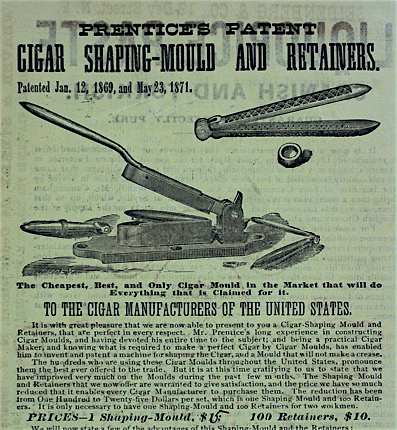

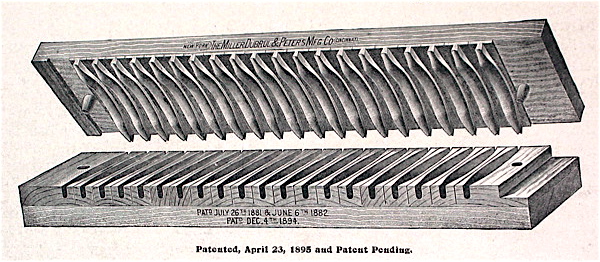

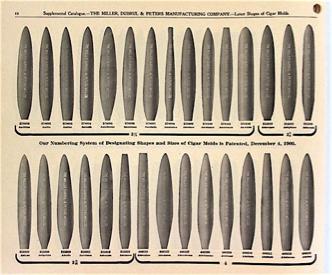

Cigar Moulds (also spelled Molds)

Manufacturing cigars by hand isn’t easy. Although the steps seem simple, making a perfect cigar, one that looks good and draws easily, requires experience and skill. As sizes and shapes proliferated in the 1830’s, it became even more difficult. Most cigar rollers came to grips with that dilemma by specializing in only a few of those sizes and shapes.

The Cigar Makers International Union recognized the difficulty of crafting high grade cigars by requiring a three year apprenticeship before granting full membership, attainment of which was certification of skill to a potential employer.

Mechanical production of cigars that were properly shaped and puffed well became a goal, and back-yard tinkerers began a chase for the fortune that would flow to the man who solved the problem. Though a few inventors tried early-on to develop a fully automated machine, history shows that automation happened in a series of steps, some more important than others. The development of machinery is the topic of another National Cigar Museum exhibit.

The first step to be solved centered on creating a device that would help less skilled, less experienced, less costly workers create cigars in the huge range of sizes and shapes the public demanded. As with most beginning industries, hundreds of experiments were tried before one method prevailed. Between 1850 and 1890 a flood of devices were offered.

Adoption wasn’t painless. In fact, at times, it was downright bloody, especially in New York City. The Union declared moulds were machines, forbad members from working in shops where they were employed, and went out on strike whenever moulds were introduced. Whatever the resistance, the mould was as inevitable as sunrise. Factory owners loved the ability to hire unskilled (less costly) labor, the shorter training period (as low as a month), and cheaper manufacturing costs which moulds permitted. A highly skilled and well-paid hand roller working quickly by himself could make from 250 to 350 cigars a day. However, if he did nothing but apply the outside wrapper to bunches created by a team of two semi-skilled mould workers, he could turn out 750-1000 a day. Three people still made the same number of cigars, but mould workers got paid less, often one-fifth as much, so a cigar company could cut its labor cost substantially without cutting production. Moulds also widened the base of available workers by bringing women into the workforce in great numbers.

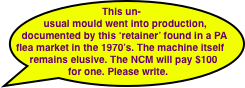

There is some debate over one-cigar moulds like these. John Kline, writing about cigar tools in the 1970’s, describes them as possibly being salesmen’s samples. Personally, I believe them to be failed types of early mould, and collect them for the Museum as such.

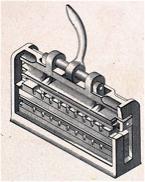

The mould in the middle is used to press flat and put the bend in Crooks. The German mould on the right allows the cigar roller to form 25 eight-inch long double-headed cigars, then run a knife down the middle of the mould and end up with 50 standard (100 years ago) four inch long smokes with an open tuck.

Close up of a closed two-piece mould with Miller Dubrul & Peters markings. Early moulds are found without Peters’ name.

An ironic twist of fact: when automated cigar making machines were introduced, mould-made cigars, once the subject of riots, were no longer thought of as “machine made” cigars. The definition changed, and mould-made cigars were reclassified as “hand made” (what they’re called today).

Occasionally you’ll find a mould with labels pasted on. In a factory that might make 50 or more brands, this was a simple way to keep track of which brands were made in which moulds. This mould not in the NCM collection.

How rare are moulds? Although oddities like the single cigar moulds above are scarce, moulds in general are common. A million or more were sold every year for half a century and in lesser quantities for another 100 years. Because they were made of premium hardwood, almost always maple, outdated or damaged moulds were commonly burned for heat in the factory’s pot-bellied stove during chilly Northern winters. Even so, they have survived by the tens of thousands. They are logically the most common the the states with the most cigar factories: New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, New Jersey and Florida, but are likely to turn up anywhere. What are they worth? $20 to $30 unless in some way unusual. Modern moulds are frequently made of plastic, said to be considerably more rugged.

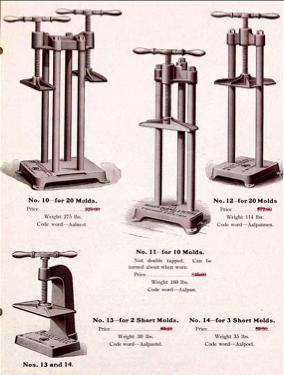

![Mould Press

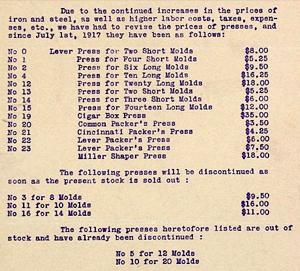

For the relatively short time that the partially made (unwrapped) cigars spend in the mould (about 30 minutes) it is necessary to keep the moulds compressed so that the cigars don’t expand and become misshapen. Moulds are pressed by a tool called, not surprisingly, a mould press. Just as moulds are made in a large number of sizes, so too are presses, complicated by the fact that presses are designed to hold varying quantities of moulds.

The page left is one of four describing presses in MD&P’s 1904 catalog. The 1919 MD&P letter (above) reports the press top left has been discontinued, the press top middle is about to be, and the price of the press top right which weighs 114 pounds and can hold 20 moulds, has been raised from $12 to $18. The press lower left comes in two sizes, for 2 or 3 short moulds, and has doubled in price.

Each worker’s bench is equipped with a small press holding two short moulds, while the roller fills a third mould. When the 3rd is full, it is traded for one in the press. The partially finished cigars, called “bunches, are removed and the wrapper applied. Wrapper may be applied by the person who formed the bunch or by someone else.

Since the appearance of the cigar depends on the skill with which the wrapper is rolled on it is frequently applied by an experienced, and more highly paid, specialist.

When two rollers make bunches and as third applies the wrapper it’s called “teamwork.” For decades, Union members were forbidden to be part of a team.

This small combination desktop press and mould was invented in the 1870’s. Though conveniently sized and shaped, it doesn’t seem to have caught on. It has been seen in an illustration or two, but none seem to have survived. Should you find one, the Museum would be interested in obtaining it for study and display.

[5069]](Hand_tools_files/shapeimage_7.png)

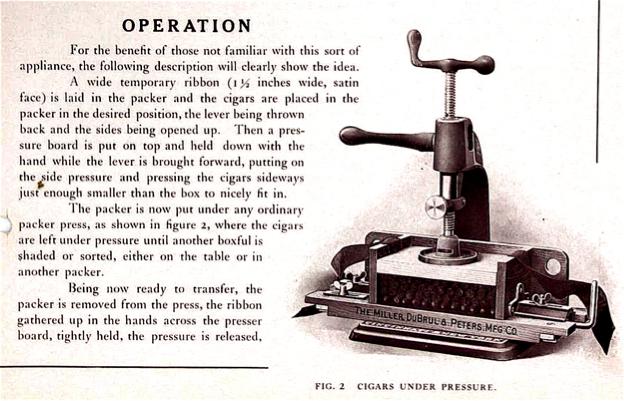

Packer’s Boxes & Presses

Retired cigar maker Bob Frutiger explains: “In the Frutiger factory we called these a Packer’s Box. After the wrapper had been applied and the cigars were finished, they were tied in bundles of 50. A skilled worker with a good eye for color, called a “packer,” then untied the bundles and sorted the cigars by color. When the packer was done sorting a bundle for color he reached for a box like this. The packer would put a strip of paper 3 inches wide and 20 long lengthwise in the empty box, the ends hanging out. Then the color graded cigars were put in the box. If the color wasn’t specified we put the lightest colored and best looking cigars on the top row of the box. If the order was for dark cigars, the lightest ones were put on the bottom. The box gave the packer the opportunity to make certain cigars were of proper and uniform length, and all left hand or right hand rolled. Each layer was separated with a piece of reusable cardboard.”

“After the cigars were placed in the Packer’s Box, the box was put in a packer’s press (lid open), a board on top. The box was left in the press only till the next 50 cigars were graded. At that point the packer’s box was removed from the press and the lid was closed and the metal strap put in position to hold the box closed. The cigars were held several days in the Packer’s Box and then were taken to the cellophane room where the Packer’s Box was opened and all the cigars were lifted out (using the paper strap) and placed in a hopper on the cellophane machine. The Packer’s BOX was used when we made cigars by hand. We switched to Cigar Trunks when we converted production to machines.”

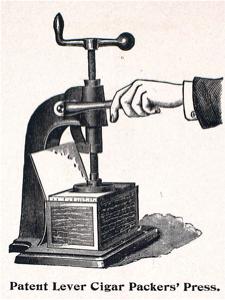

The Packer’s Press (above right) is the common screw type. Note that here the cigars are being pressed in a trimmed retail box rather than a Packer’s Box.

Lever action Packer’s Presses (lower right) had the advantage of being able to be set up for repetitive packing of boxes of the same depth. A levered press cost more than twice as much as screw type called “the common packer’s press.”

Cigar Trunk

“At Frutiger’s factory,” says Bob Frutiger, “we called these a Cigar Trunk. When machine made cigars were finished we put them in these “trunks” to dry before being cellophaned and packed in trimmed retail cigar boxes. In the old days when all our cigar boxes were made of wood and nailed tightly we did not use trunks. But cardboard boxes would burst when unshaped cigars were packed in them, so the cigar drying trunk was born. We held cigars in the trunk for at least three days. Sometimes we’d hold cigars for up to a month waiting for an order for that particular size and shape. We sold the same cigar under 20 or more different labels.”

[N1179]

Shaper Press

Shaper presses were the equivalent of owning a packer’s box and side to side packer’s press in one tool. It was used in combination with a packer’s press to compress cigars getting them ready for packing in their final box. It was fairly expensive, and not used in many factories.

The MD&P ad below displays a different model and explains how they were used.

[N1226] [4856]

Repacking Machine

Doesn’t look like what we normally mean by a machine, but two different tool company catalogs call it that. The Miller, Dubrul & Peters catalog reads: “No packing-room should be without one of these handy little devices; it holds the cigars together in turning them out of the box, so avoiding the laborious packing of each separate cigar on such occasions. The re-packer is adjustable to any ordinary box.” Price, 80¢.”

[4891]

Head Shaper

A tool you’re unlikely to find is this 1871 head shaper designed by its inventor to be attached to the board or the end of the tuck cutter and used to make the head of a cigar smooth and uniform.

Find one and I’ll give $150 for it.

[4949]

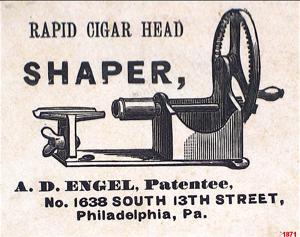

Hole-in-the-Head Machine

This 1889 flyer advertises the hand-operated patented perforator sold by cigar tool supplier Bernhardt & Co. of Newport, Kentucky. “One of these machines operated by a boy will perforate as many Cigars as a hundred or more hands can make.”

The NCM is seeking pictures and artifacts for an exhibit about the hole-in-the-head.

Especially wanted are table top hand operated machines. I’ll pay $100-$200 for one.

Scale

Retired cigar maker Bob Frutiger explains “ We used a scale to control the amount of filler in our cigars. We would weigh bundles of 50. Too heavy and the cigars would not draw properly; too light and cigar would burn fast and not hold a ash. We had a list of correct weight for every shape and ring gauge. I do not remember ever throwing out cigars for being the wrong weight but we would adjust machines to correct them if their cigars weighed too much or too little.”

“When we ran machines we would check a bundle from each machine morning and afternoon, more often if there was a problem. With hand workers we kept track of all tobacco. Each bunch-roller got a weighed amount of binder in the morning and at the end of the day we checked to see if he had made the proper number cigars per pound of binder. The same with rollers. If they used too much wrapper for the number of cigars they turned in, it was deducted from their pay.”

[10460]

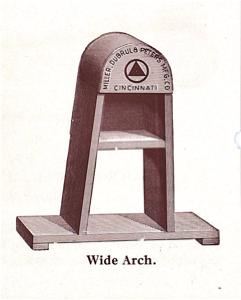

Booking Block

Preparing to make a cigar begins with growing, harvesting, drying, curing, sweating... more and lengthier handling of tobacco than most folks realize. Once tobacco is ready for the actual assembly of a cigar, the first step is the removal of the center rib in the leaf, separating the leaf into left and right hand sides. This procedure is called stripping, and is almost exclusively the role of women. This 19th century drawing shows the natural utility of a woman’s thigh. But a tool called a booking block led to more uniformity and smoother leaves.

After the mid rib was removed the leaves were smoothed over the rounded arch of the block. A mechanical version was operated with a foot pedal and could hold the leaves in place once smoothed. When 50 leaves were accumulated they were tied with a cloth strip and distributed to the cigar rollers for use.

Brass Clamp

“When bales of tobacco were opened, the leaves were hard and dry. At Frutiger’s, we took one hand (tied bundle of 35-80 leaves) at a time and held it in front of water mist. At this point the tobacco was still hard and brittle. We had a 5' X 5' X 10’ closet with over 100 clamps mounted in rows on the back wall. The moistened hand of tobacco was placed in the clamp and left to become uniformly moist and workable. This took at least 24 hours,” reported Bob Frutiger.

Date Cancellers

Not part of manufacture, nor part of packing, but a stamp canceler was still a commonly found tool in cigar factories because Federal law required that tax stamps be dated and cancelled before the finished sealed retail box of cigars left the factory. This type of rubber canceler was first permitted in the 1870’s, replacing pen and ink hand cancellation. The pictured canceler has a rectangular center, but circles were more common. An example of the latter can be seen in the exhibit of US revenue stamps <here>.

Hand stamp cancels were largely replaced by perforation cancellation in larger factories after 1910, though both styles remained legal as long as stamps were used. A stack of 5 to 10 stamps was punched at once. The January 33 date is a misprint.

Perforator pictures

are courtesy of

Bob Frutiger.

The NCM does not

own one of these

canceling machines

but would like to.

TEST YOUR POWERS OF OBSERVATION:

How do you tell a mould press from a packer’s press?

Both look the same. Both are cast iron. Both have screw adjustments. Both may or may not have levers.

ANSWER: The answer is at the base of the screw. Packer’s presses are used with boards cut to fit the exact size of the box being pressed, so the base of the screw is round and small, about 3 inches in diameter. Mould presses need to disburse force over a longer area and so have a wide long rectangular plate.

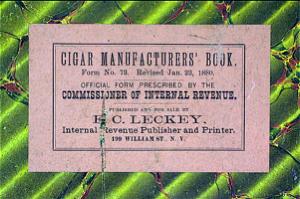

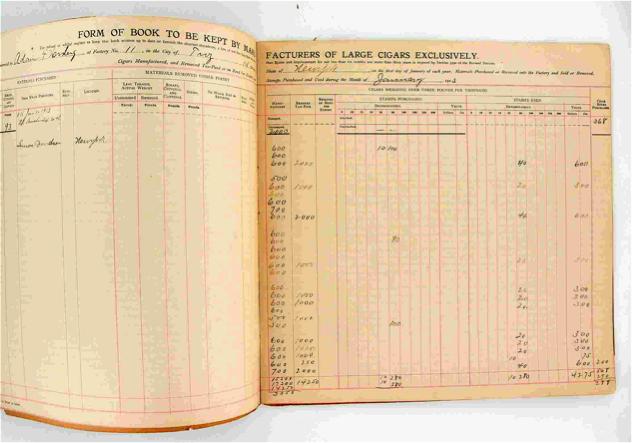

Government Required Paperwork

Every small businessman or woman will attest that an entrepreneur’s worst enemy is the U.S. Federal Government. Between OSHA, FICA, IRS, ADA and an alphabet soup of other evils the most difficult barrier to success lies along the Potomac. Ask any company’s business office and they’ll report that half their time (or more) is spent dealing with government forms, regulations and tax matters. Those politicians and others who long for days gone by, waxing eloquently about about elysian fields of the past, alas, show an abysmal lack of historical knowledge, as government regulations have never been kind.

No one knows this better than someone involved in tobacco, one of the most heavily regulated industries since the 1700’s. Among tools essential to the survival of any cigar maker must be counted the licenses, tax forms and ledgers required by Uncle Sammy.

The pictured ledger is from 1912-1913 and measures 11” high by 24” wide. Columns, left to right: Date / Leaf Tobacco Actual Weight Unstemmed pounds on hand / Leaf Tobacco Actual Weight Stemmed pounds on hand / Scraps, Cuttings and Clippings pounds on hand / Materials Purchased - from Whom Purchased - Business - Location / Leaf Tobacco Removed Actual Weight Unstemmed pounds / Leaf Tobacco Removed Actual Weight Stemmed pounds / Scraps, Cuttings and Clippings pounds removed / Stems pounds removed / To whom sold or returned - Business - Tax District & State / Cigars Weighing more than 3# per 1,000 Manufactured / Cigars Weighing more than 3# per 1,000 Removed Tax Paid / Cigars Weighing more than 3# per 1,000 Removed in Bond for Export / Stamps Purchased - Denominations -5 -10 -12 -13 -25 -50 -100 -200 -250 -500 / Stamps Purchased Value Dollars - Cents / Stamps Used Denominations -5 -10 -12 -13 -25 -50 -100 -200 -250 -500 / Stamps Used Value Dollars - Cents / Cigar Boxes Purchased. The ledger data was required to be filled out daily. Wheeeew!

February, 1912, was a little better than average month for this Troy, NY, company. They made from 300-800 cigars daily six days a week, sold 1,000 to 2,000 a week and used only boxes and stamps for 50 cigars. They bought 738 empty cigar boxes during the Month.

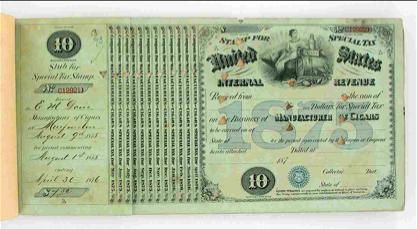

Special Tax Stamp

Special doesn’t mean short lived. This type tax amounting to a license was required for more than 50 years. The stub on the left was kept by the tax collector and the license was to be hung in the shop. The middle strips are trimmed to show the months for which the license was paid. These fees were required each fiscal year, starting when the business was begun.

Many different forms of similar licenses were issued to manufacturers, brewers, distillers, peddlers and other retailers of all forms of tobacco and liquor. During the 1870’s and 80’s these were released to collectors after the government voided them by punching holes. As a result they exist in rather large quantities for those dates. Of more interest are used licenses and tax collector’s booklets containing filled out stubs or stamps from other dates.

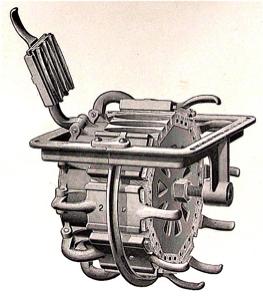

Revolving Mould

L:[4887]

R:[11112]

A partly finished cigar consisting of filler wrapped in a binder leaf to hold it together spends about a half hour in a pressed mould, about time for a roller to fill two more moulds. Some clever soul created a revolving mould roughly the size of three moulds that took less space and was mould and press in one tool. The one on the left was built into a table, the one on the right was free-standing.

Bundling Rack