White Labor

A Cigar History Museum Exhibit

© Tony Hyman

White Labor

A Cigar History Museum Exhibit

© Tony Hyman

[10215]

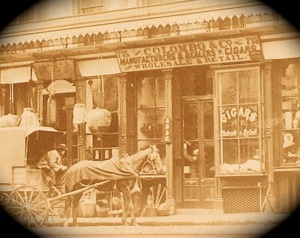

From an 1875 cigar

box made in Calif.

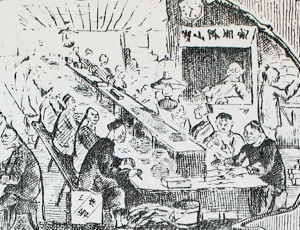

To read a description of a Chinese cigar factory in

an 1897 San Francisco newspaper...click here

SOME NUMBERS

[10173]

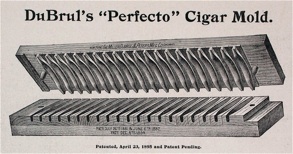

Magazine ad;

1886 issue

of The Wasp

published by

Korbel who

went on to

winery fame.

Info from McCunn, Saxton, Chiu, Trade Directories, period newspapers, other sources

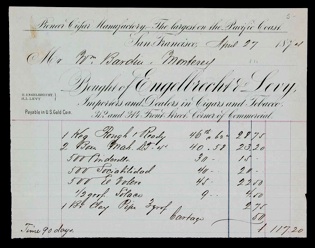

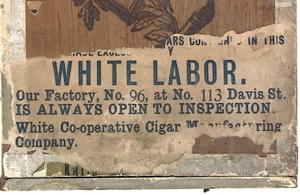

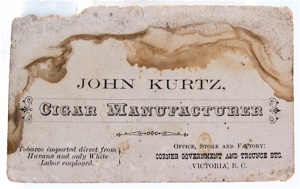

This rare

business card

was found in

the walls of

a log cabin

in the woods

of British

Columbia in

the 1980’s.

Western

Canada was

home to many

Chinese and

their history

is similar in

many ways.

[0000]

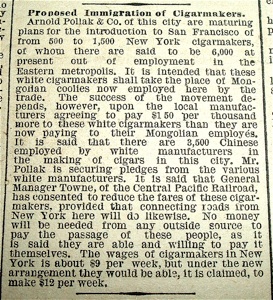

The President of the San Francisco Union Local traveled east and recruited a disappointing 400 rollers to come to California by offering reduced railroad fares. The imported workers discovered West Coast wages to be less than promised, rebelled, demanded raises from $2 to $4 per thousand cigars.

With few exceptions the Easterners were not successful, factories continued to employ Asians, and within a year most of the Union men returned to their homes in the East.

Ultimately, local harassment and the Chinese Exclusion Acts of 1882 drove many Chinese out of the cigar business, into more profitable and less contentious industries. It has been claimed by modern writers that when the Chinese left so did the vitality of the California cigar industry, but data doesn’t bear that out. Golden State production surpassed that of Florida until the 20th century, remaining in the top 15 cigar states until the machine age began after World War One.

Chinese were also employed in the cigar box industry, manufacturing about 1/6th of all California-made boxes in 1881. In 1904, there were five box factories in San Francisco, employing 140 workers,

80 of whom were Chinese.

nnn

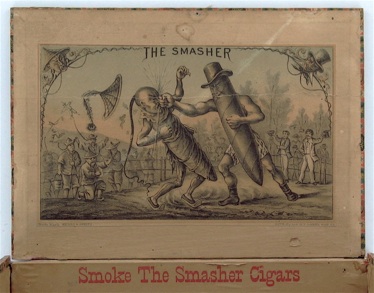

[0000] Walk races were a popular sport in the 1870’s, the decade of this card

ridiculing cigars made by Chinese or made in NYC tenement houses.

[0000]

[0000]

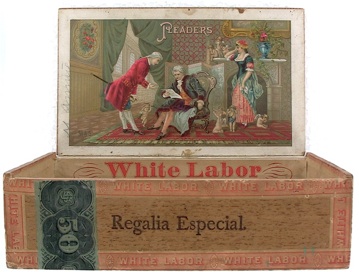

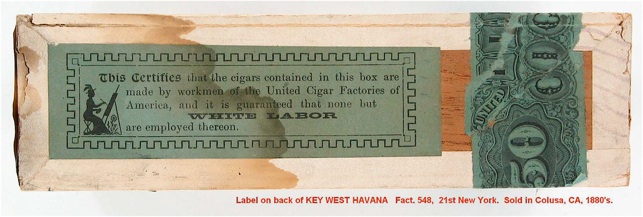

KEY WEST HAVANA cigars made in Western NY,

sold in Colusa, California gold country in 1883.

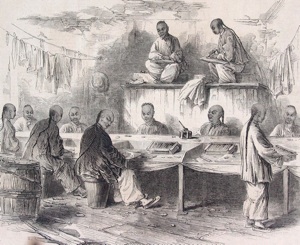

[10172] Chinatown cigar factory [0477] Chinatown factory interior

[1681]

[

[1680]

By 1868, the annual value of San Francisco-made cigars had risen from a few thousand dollars to more than a million and California had replaced Massachusetts as the fourth largest cigar producing state.

Other white factory owners, especially larger ones, began hiring Chinese, who made up 8% of California’s population but 25% of the available work-force-for-hire.

By 1870, just eleven years after Englebrecht and Levy made their fateful offer, the Chinese were respon-sible for 80% of the cigars rolled west of the Rockies. Chinese-owned companies began opening new factories in Boston, New York and Vancouver.

Opinions about the quality of Chinese cigars differ. Some modern writers claim the cigars were as good, but that certainly wasn’t the image promulgated by the white factories. Cigarmakers nation-wide viewed the chinese as a symbol of the drop in quality when moulds were permitted.

A decade of particularly violent anti-Chinese sentiment began.

[10179]

In 1860, the Englebrecht & Levy factory with its Chinese workers was booming. Business had never been so good. But, during the next few years the partners learned they had made an irreversible mistake. The men they hired were not, as they assumed, coolies from the bottom of the Chinese social ladder. Many were well educated Chinese business and professional people anxious to learn the secrets of cigar making as their opening to living the American dream. They learned their lesson well.

No evidence exists as to when moulds arrived

in the U.S. Some writers claim a date as late as 1870. Most place it in the 1860’s. If you care, write me and I’ll explain why I think it’s earlier. [4991]

In 1874, the friends were still in business.

Cigars wholesaled from 3¢ to 4.5¢ each. [10176]

The two partners discussed their options for weeks before deciding to take advantage of the surplus of cheap Chinese labor. Once this radical decision was made, the two entrepreneurs pasted posters throughout Chinatown, promising to teach a valuable new trade to accepted applicants.

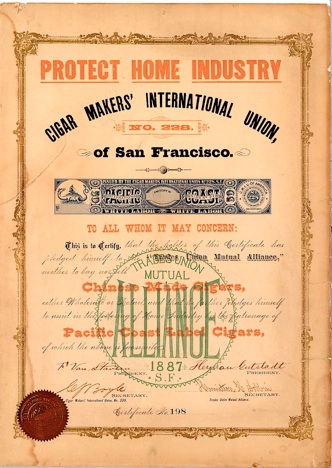

I887 CMIU ANTI-CHINESE WINDOW CARD

PROTECT HOME INDUSTRY

CIGAR MAKERS’ INTERNATIONAL UNION

NO. 228

of San Francisco

TO ALL WHOM IT MAY CONCERN:

This is to Certify, that the holder of this Certificate has pledged himself to the “Trades Union Mutual Alliance,” neither to buy nor sell Chinese Made Cigars, either Wholesale or Retail, and that he further pledges himself to assist in the fostering of Home Industry by the patronage of Pacific Coast Label Cigars, of which the above is facsimile.

TRADES UNION MUTUAL ALLIANCE 1887 S.F.

F. Van Stavern, President

C.M Boyle, Secretary

CMIU local 228

Herman Gutstadt, President

Hamilton Dobbin, Secretary

Trades Union Mutual Alliance

Alas, card & stamp not in the NCM collection.

Seen courtesy of Brian Roberts.

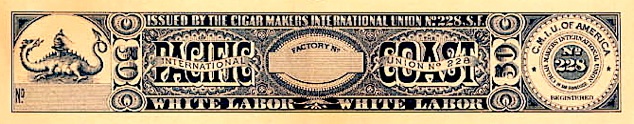

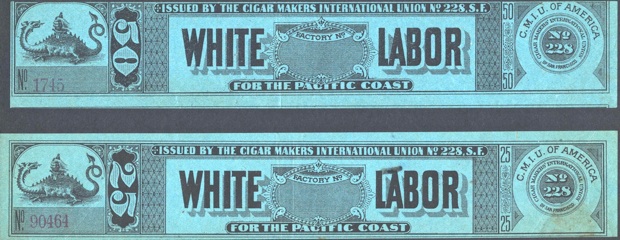

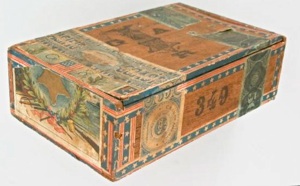

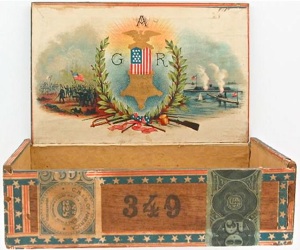

The organization of Civil War Veterans called the Grand Army of the Republic, usually shortened to G.A.R., held their 20th annual convention in San Francisco. Just as the election of 1888 resulted in the most election-related boxes, the encampment (for that’s what their reunions were called) of 1886 resulted in the most G.A.R. boxes. The one seen here has the distinction of being the first box of any type yet found displaying the “White Labor” stamp (top) issued by Cigar Maker’s Union Local 228. Note the blank in the center for use by members of the Local to put their factory number. In this case Factory # 349, 1st tax district of California made the cigars.

Unfortunately, records are unclear, but as best as best as they can be interpreted the factory was owned by A.S. Blick, 7 Spear St., in San Francisco, who made the cigars for wholesaler / retailer J.W. Shaeffer and Co.

The black ink on blue paper variations seen here have yet to be found on a box, whereas the top stamp is used on the box (right). Both are rare, on or off a box. I’d love to find them.

The two blue variants are not in the NCHM collection and seen courtesy of collector Hermann Ivester.

[17208]

[17204]

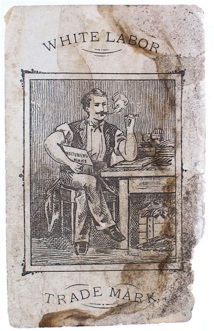

White factories that survived the Chinese incursion tended to be small marginal factories who were struggling against better capitalized large companies as well as the Chinese. These cigar makers formed affiliations such as The White Co-Operative Cigar Manufacturing Co., pledging to fight what they saw as encroachment on both cigar quality and racial purity. Promoting White Labor with newspaper ads, business cards and box labels proclaiming their cigars to be hand made in a white factory by white workmen became important ways to differentiate their product. Placards were posted in stores that committed themselves to boycott Chinese-made goods (below). During the heart of the depression of the 1870’s, support from the anti-Chinese segment of the population kept them going. Their drive was so effective that Eastern cigar makers began adding “WHITE LABOR” notations on their boxes to help them sell in the California market.

[9085]

Factories employing Chinese mould-workers defended themselves, pointing out there weren’t enough white workers to fill their factories.

In the early 1880’s The Cigar Makers’ Union entered the fray, demanding that factories fire Chinese workers as of January 1, 1886, or as soon as white workers became available. In exchange the CMIU pledged to provide skilled rollers.

This story on the front page of the San Francisco Evening Bulletin (June 5, 1882) reports the goal was to recruit 500 to 1,500 rollers from New York City in an effort to help replace the 3,500 Chinese then working in the City by the Bay.

The original of this paper is not in the NCM collection.

In 1876 a San Francisco cigar maker in his testimony before the Joint Special Committee of Congress to investigate Chinese Immigration estimated the number of Chinese cigar makers in San Francisco at over 6000 and the number of white cigar makers at 150. The Chinese figures may be exaggerations, considering he was seeking relief from Congress. The average Chinese cigar roller earned, according to a Cigar Makers’ Union repart, about six dollars a week, while the whites earned $8 to $10, less than they made in the East, where a first rate roller could make as much as $20.